Circe (Masterpics / Alamy)

Images of alluring young witches and hideous hags have been around for centuries – but what do they mean? Alastair Sooke investigates.

Ask any Western child to draw a witch, and the chances are that he or she will come up with something familiar: most likely a hook-nosed hag wearing a pointy hat, riding a broomstick or stirring a cauldron. But where did this image come from? The answer is more arresting and complex than you might think, as I discovered last week when I visited Witches and Wicked Bodies, a new exhibition at the British Museum in London that explores the iconography of witchcraft.

Witches have a long and elaborate history. Their forerunners appear in the Bible, in the story of King Saul consulting the so-called Witch of Endor. They also crop up in the classical era in the form of winged harpies and screech-owl-like “strixes” – frightening flying creatures that fed on the flesh of babies.

Circe, the enchantress from Greek mythology, was a sort of witch, able to transform her enemies into swine. So was her niece Medea. The ancient world, then, was responsible for establishing a number of tropes that later centuries would come to associate with witches.

The Three Weird Sisters from Macbeth, 1785 (The Trustees of the British Museum)

Yet it wasn’t until the early Renaissance that our modern perception of the witch was truly formed. And one man of the period arguably did more than any other to define the way that we still imagine witches today: the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer.

Double trouble

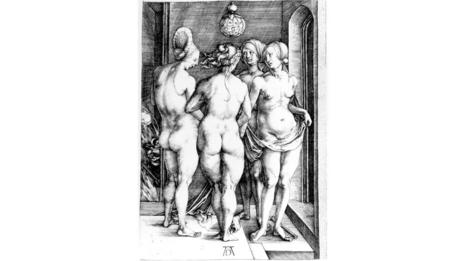

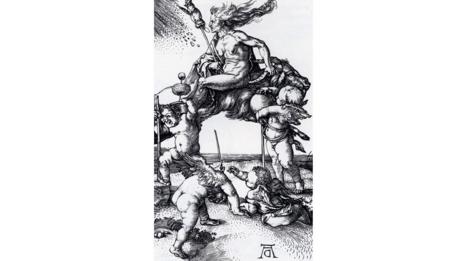

In a pair of hugely influential engravings, Dürer determined what would become the dual stereotype of a witch’s appearance. On the one hand, as in The Four Witches (1497), she could be young, nubile and lissom – her physical charms capable of enthralling men. On the other, as in Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat (c 1500), she could be old and hideous.

Durer's influential etchings portrayed witches as young and nubile or old crones (Albrecht Dürer)

The latter print presents a naked crone sitting on top of a horned goat, a symbol of the devil. She has withered, drooping dugs for breasts, her mouth is open as she shrieks spells and imprecations, and her wild, wind-blasted hair streams unnaturally in the direction of her travel (a sign of her magical powers). She is even clutching a broomstick. Here is the matriarch of the witches that we find in popular culture today.

For art historians, though, the interesting question is what provided Renaissance artists with the model for this appalling vision. One theory is that Dürer and his contemporaries were inspired by the personification of Envy as conceived by the Italian artist Andrea Mantegna (c 1431-1506) in his engraving Battle of the Sea Gods.

“Mantegna’s figure of Envy formed a kind of call for the Renaissance of the witch as a hideous old hag,” explains the artist and writer Deanna Petherbridge, who has co-curated the exhibition at the British Museum. “Envy was emaciated, her breasts were no longer good, which is why she was jealous of women, and she attacked babies and ate them. She often had snakes for hair.”

Another of Durer's etchings shows a witch riding backwards on a goat, with four putti (The Trustees of the British Museum)

A good example of this Envy-type of witch can be seen in an extraordinarily intense Italian print known as Lo Stregozzo (The Witch’s Procession) (c 1520). Here, a malevolent witch with open mouth, hair in turmoil and desiccated dugs clutches a steaming pot (or cauldron), and rides a fantastical, monstrous skeleton. Her right hand reaches for the head of a baby from the heap of infants at her feet.

This print was produced during the ‘golden age’ of witchcraft imagery: the tumultuous 16th and 17th centuries, when vicious witch trials convulsed Europe (the peak of the witch-hunts lasted from 1550 to 1630). “Across Europe, there was the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, the Thirty Years’ War, fantastic poverty and social change,” says Petherbridge. “Even King James in his text Daemonologie [1597] was asking: why was there such a proliferation of witches? Everybody assumed it was because the world had got so foul that it was coming to an end.”

As a result there was an outpouring of brutally misogynistic witchcraft imagery, with artists taking advantage of the invention of the printing press to disseminate material rapidly and widely. “Witchcraft is closely allied to the print revolution,” Petherbridge explains. Many of these prints, such as the powerful colour woodcut Witches’ Sabbath (1510) by Dürer’s pupil Hans Baldung Grien, can be seen in the British Museum’s exhibition.

By the 18th Century, though, witches were no longer considered a threat. Instead they were understood as the superstitious imaginings of peasants. Still, that didn’t stop great artists such as Goya from depicting them.

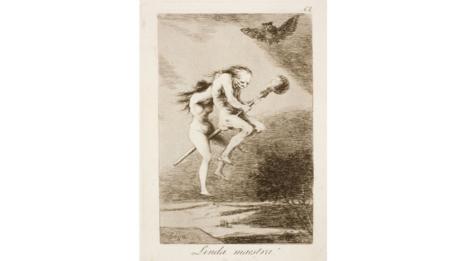

Los Caprichos is Goya’s collection of 80 etchings from 1799 that use witches as vehicles for satire (Goya)

Los Caprichos, Goya’s collection of 80 capricious (or whimsical) etchings from 1799, uses witches as well as goblins, demons and monsters as vehicles for satire. “Goya uses witchcraft metaphorically to point out the evils of society,” says Petherbridge. “His prints are actually about social things: greed, war, the corruption of the clergy.”

Broom with a view

Goya did not believe in the literal reality of witches, but his prints are still among the most potent images of witchcraft ever made. Plate 68 of Los Caprichos is especially memorable: a wizened hag teaches an attractive younger witch how to fly a broomstick. Both are naked, and the print was surely meant to be salacious: the Spanish ‘volar’ (to fly) is slang for having an orgasm.

Around the same time, there was a vogue among artists working in England for depicting theatrical scenes of witchcraft. The Swiss-born artist Henry Fuseli, for instance, made several versions of the famous moment when Macbeth meets the three witches for the first time on the heath.

By now, though, the art of witchcraft was in decline. It lacked the strange imaginative force that had animated the genre in earlier centuries. In the 19th Century, the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists were both drawn to the figure of the witch, whom they recast as a femme fatale. But their sinister seductresses arguably belong more to the realm of sexual fantasy than high art.

The one constant throughout the history of the art of witchcraft is misogyny. As a woman, how does this make Petherbridge feel? “At the beginning when I was looking at these images, I was quite distressed because they are so ageist,” she says. “Of course, now I’ve stopped being shocked by them, and I think that they are saved by their excess, satire and invention. Artists were often drawn to these scenes because they offered drama. They were free to spread their wings and come up with all kinds of bizarre imagery. Yes, these scenes represent the demonisation of women. But often they are keenly linked to social critique. Witches are the scapegoats on which the evil of society is projected.”